Nellie Grant

Bruce Catton, the noted Grant biographer, once remarked that Ulysses S. Grant's daughter, Nellie (1855-1922), had a "particularly secure place in his heart." She was his only daughter, and was surrounded by affection and attention. Grant was openly demonstrative with Nellie and showed her a quiet consideration that was conspicuous. His fatherly devotion to her was touching to all who observed it. He had a number of nicknames for her, including "Missy" and "Martha Rebecca." In letters he wrote to Julia, his wife, he sometimes referred to Nellie using these different pet names.

Nellie at the age of 12 Nellie at the age of 12

Everyone who knew Grant recognized that Nellie was his favorite child. His wife admitted it in her memoirs, as did his sons in interviews from later years. An example of Grant's affection for Nellie appears in the August 17, 1873 issue of the Portsmouth Ledger, as the Grants passed through New Hampshire. A reporter was onboard a train as the President traveled to Augusta. He wrote, "President Grant arrived on the new Pullman car "Mystic" with the usual dignitaries and his children. Miss Nellie Grant... who is 17 years old, held her father's hand throughout the journey. When a baggage handler became too inquisitive towards the fair daughter, the General showed positive annoyance and held Miss Grant ever-closer to the Presidential bosom."

Nellie as the "Old Woman in a Shoe" in 1864 Nellie as the "Old Woman in a Shoe" in 1864

Nellie's teenage years were uneventful, though it was occasionally noted in the press that she was too fond of partying, staying out late and doing other things teenagers are prone to do. She briefly attended boarding school, but became so lonesome without her parents that she returned home within days. The Grants youngest child, Jesse, also lasted only two days at his boarding school, before returning to the White House.

Nellie and Jess in 1869 Nellie and Jess in 1869

Nellie married an Englishman named Algernon Sartoris in 1874 and moved to England. Grant did what he could to prevent the marriage, thinking Nellie was too young to wed. He wrote a remarkable letter in July, 1873 to Nellie's future father-in-law, Algernon Sartoris, Sr., in which he tries to ascertain whether Algie had a past with women and whether he was likely to remain in England. Grant wrote, "an attachment seems to have sprung up between these two young people, to my astonishment because I had only looked upon my daughter as a child, with a good home which I did not think of her wishing to quit for years yet. She is my only daughter and I therefore feel a double interest in her welfare...I hope you will attribute any apparent bluntness to a fathers anxiety for the welfare and happiness of an only and much loved daughter."

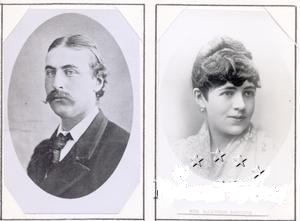

The dreaded Algernon Sartoris with Nellie, after their marriage. The dreaded Algernon Sartoris with Nellie, after their marriage.

After her marriage in the White House, Nellie generally spent the summer with her parents and remained close to them, exchanging frequent letters. When Grant realized he was dying of throat cancer in the winter of 1884, Nellie was still living in England with her children. He was loath to summon her to his side, as that smacked of a maudlin death bed vigil, but he had no choice. He knew he was dying and he wanted her to be by his side. Five months before his death, and suffering intense agony from his throat malady, Grant wrote Nellie a touching letter.

Though he didn't implicitly ask her to sail to America, she undoubtedly got the message, because she arrived in New York exactly 16 days after it was written. Considering that the crossing of the Atlantic ocean consumed seven days and mail delivery was not then advanced, she must have made a hasty exit from the Britain. Despite his suffering, the General personally greeted his daughter at the dock, embracing her with tear streaked eyes. The following letter has never before been published.

February 16, 1885

Dear Nellie,

Your letter of the second of February, to your mother, came two or three days ago. Algy (Grants son-in-law) arrived a few days before and came up and stayed with us until after dinner. All the family are well except me. The sore throat which you recollect I had all the time we were at Long Branch last summer has proven to be a very serious matter. I paid no attention to it until it had been four months. I found then the doctors considered it a very serious matter. Even now I have to see them twice a day.

It has troubled me so much to swallow that I have fallen off nearly 30 pounds. It has only been within the last two days that the doctors have been willing to say that the ulcers in my throat are beginning to yield to treatment. It will be a long time yet before I can possibly recover.

It be would be very hard for me to be confined to the house so long a time if it was not that I have become interested in the work which I have undertaken. It will take several months yet to complete the history of my campaigns. [Note: Grant is referring to his Memoirs which he was then writing] The indication now are that the book will be in two volumes of about 450 pages each. I give a biography of my life up to the breaking out of the Rebellion. If you ever take the time to read it you will find out what sort of a boy and man I was before you knew me.

I do not know whether my book will be interesting to other people or not, but all the publishers want to get it, and I have had larger offers than have ever been made for a book before. Fred helps me greatly in my work. He does all the copying and looks up references for me. We have all been as happy as could be expected considering our great losses and my personal suffering. Philosophers profess to believe that what is for the best. I hope it may prove so with our family.

All join me in sending love and kisses to you and all the children.

Your affectionate Papa

This letter, along with 33 others that Grant wrote Nellie, is available for viewing at the Chicago Historical Society, a treasure trove of original Grant documents.

|